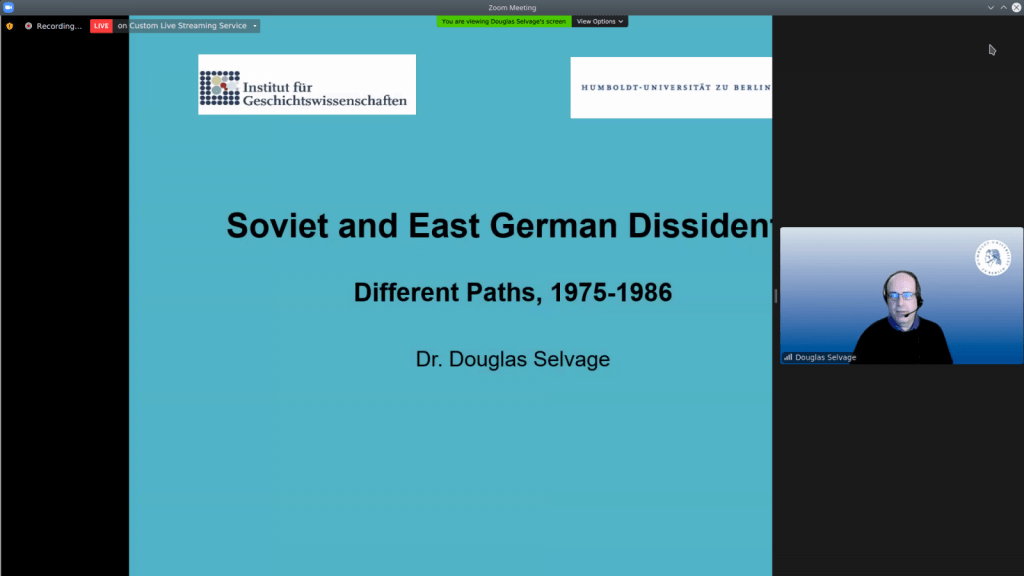

The webinar “Dissidents and Human Rights Behind the Iron Curtain: Dissidents in East Germany and the Soviet Union Partners” was held on February 22nd, 2021 and featured Aryo Makko, Director of the Hans Blix Center at Stockholm University as moderator. The guest speakers were Professor Norman Naimark of Stanford University, Professor Douglas Selvage of Humboldt University Berlin and Professor Henrik Bispnick, also from Humboldt University Berlin.

The first speaker, Professor Norman Naimark, addressed the topic “Comparison of dissidents in the GDR and the Soviet Union.” According to Naimark, it is problematic to define dissidents, starting with the dictionary which states that they are people who are in opposition to the government, many in Democratic Germany and even more so in the Soviet Union. It is a very broad term that has many meanings and we are not sure of the “true” one. Sakharov considered himself a physicist and not a dissident, for example. Many of the similarities between dissidents in the Soviet Union and democratic Germany emerge from the very similarities between the two systems; a single party holding power. Naimark also addressed the KGB and Stasi, the secret police in both the Soviet Union and democratic Germany, indicating that their systems of operation were, also, similar. In relation to dissidents, their main function was to penetrate their circles, to follow and arrest them, in order to basically prevent them from doing their jobs. According to Naimark, the police did not know how to deal with the dissidents, which made the dissidents more powerful and likely to survive. The professor also referred the international context, first with the Cold War and then with Détente and Ostpolitik, which worked with the dissident movement in similar ways. It was in this context that the Human Rights movement and the debate on this very issue in the 1960s and 1970s emerged, which also became fundamental for dissidents. The differences between dissidents and their culture ultimately has to do with the culture from which they emerge.

Looking at the Soviet Union, there are two factors that “provoke” the dissident movement; the existence of the Russian secret police, the KGB and the events of the late 1960s and early 1970s regarding Human Rights. The professor states that many of the conflicts between the dissidents and the government took place in the courts. In the case of democratic Germany in the late 1960s, the party was supposed to be less bureaucratic and more humane. Naimark points the existence of West Germany, which was quite different from the Soviet Union in cultural and social terms. For Naimark there was a big difference between the Church in the Soviet case and in the case of democratic Germany; the Russian Orthodox Church was subordinated to the state; penetrated by the KGB, it was not a place where dissidents could find support or help. On the contrary, in the case of the Lutheran or Anglican Church in democratic Germany, this place was one of the most important in providing help to dissidents and aid to the peace movement during the 1970s. In conclusion, the professor states that dissidents were considered “crazy” by the regime for being against the established society and were sent to psychiatric hospitals or to labor camps, known as “gulag”, where they were supposed to learn to be good Soviet workers.

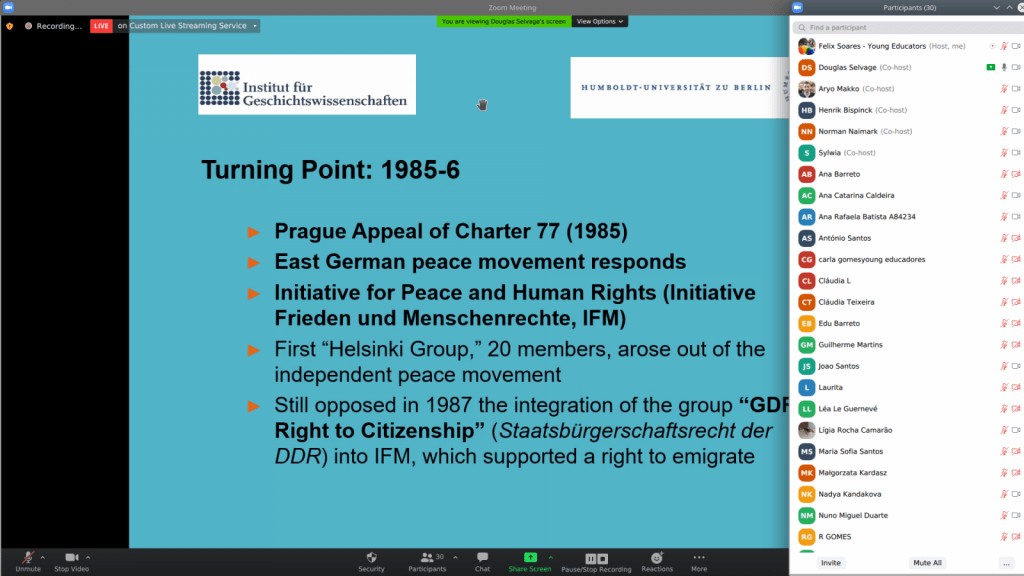

The second speaker, Professor Douglas Selvage from the University of Berlin addressed the topic “Soviet and East German Dissidents: Different Paths (1975-1986).” He points 1975 as a “turning point” in terms of encouraging dissidents and opposition, both in the Soviet Union and in Eastern Europe. Selvage recognized the importance of the Conference on European Security and Cooperation (CSCE) and the Helsinki Accords of 1975, signed by 36 states. These were a commitment to establish contacts and exchange information between East and West, as well as a recognition of existing borders. In the Helsinki Accords, one of the fundamental principles was number 7, with the indication of Human Rights. Once again it was agreed that Andrei Sakharov (1921-1989) was someone important to the issue of human rights and that Soviet Union was pressured to be an ally in the same issue. Following the CSCE, the so-called “Helsinki Groups” were formed, starting in 1976 with the Soviet Union’s “Moscow Helsinki Group”, which had as its main objective to monitor how the Soviet Union dealt with the issue of human rights after the signing of the Helsinki Accords. This was followed by other groups in various communist states such as in Poland and Czechoslovakia; “Commitee to Defend Workers (KOR) in 1976, and “Charta 77” in 1977. These groups used the “Follow-Up” Conferences to put pressure on governments to guarantee human rights to the people in their states. These conferences took place in Belgrade (1977-1978), Madrid (1980-1983) and Vienna (1987-1989). Selvage asks “what are the major differences or conflicts among Soviet dissidents?” and answers by stating that they did not believe in organizing around human rights and the CSCE until at least 1986. For the Soviet dissidents, the right to emigrate was one of the essential points that they tried to obtain from the Soviet government, basing themselves on Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Principle 7 of the CSCE Final Act. In this way, this Agreement “fuels” the emigration movement. The professor states that many dissidents were opposed to emigration because they would later not be able to return to their country or see their family again. According to Selvage, there was a “turning point” between 1985 and 1986, where the Democratic Germany’s opposition was more in the way of Human Rights with various situations of group’s formation, among which was the formation of the first “Helsinki Group” in 1986, with only 20 members. It was the birth of an independent peace movement.

Dr. Henrik Bispinck from Humboldt University Berlin was the third speaker with a presentation about “East German dissidents and their role in the peaceful revolution in the end of the GDR (1989).” Bispinck reflects on the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, indicating that this event was unexpected, yet received with euphoria by both sides of the wall. Nevertheless, in the case of the dissidents, the feeling was ambivalent. Most dissidents hoped for reforms within the system itself, and their goal was not “overcome socialism”. After November 1989, the development of democratic Germany was determined by external rather than internal factors; for example, the negotiations of the reunification of Germany or the opening of the borders to the West. The opposition played a key role for the revolution in the decisive phase between early September and early October 1989: an “alternative course of action” for leaving democratic Germany and served as the “crystallizing point” of the mass protests.

This webinar proved to be fundamental for the NoWall project since it pointed as the main topic of discussion the dissidents on the other side of the Iron Curtain. All speakers ended up complementing each other with the shared information and demonstrated the importance that the 70s have for the formation of the Human Rights movements.

Full webinar video: