In June 1957, Clarence Pickett, Norman Cousins, Saturday Review’s editor and Lenore Marshall, scheduled a meeting in New York. Among the participants were representatives from the business world, science, work, literature and church. This group of anti-nuclear peace activists pretended to guarantee an international ban on nuclear testing and adopted National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) as its name. They quickly became the largest and the most prominent peace group in the United States of America. Their initial objectives would serve to stimulate the debate about the dangers of nuclear tests, and, at the same time, this group became a leader fighting for disarmament.

For several decades, their members have been concerned with signing petitions and writing letters and advertisements in newspapers and organizing street demonstrations to pressure American leaders to stop testing and reduce the risk of a nuclear war. This movement was at the forefront of several antinuclear rallies in the 1950s and 1960s and during the Vietnam War, in November 1965. In June 1982, SANE joined the disarmament march and the rally in New York City. However, this organization’s greatest achievement was the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, suspending atmospheric nuclear tests.

References

Katz, Milton, (1986), “Ban the Bomb: A History of SANE, The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, 1957-1985 (Contributions in Political Science)”, Praeger.

Amnesty International is a non-governmental organization founded in London in 1961, by lawyer Peter Benenson, after the article “The Forgotten Prisoners” was published in The Observer on 28 May 1961. The article alerted the reader to violations by governments the Universal Declaration of Human Rights on issues such as restrictions on press freedom, political opposition, trials in impartial courts and exile. With a focus on human rights, the organization’s mission is to campaign for “a world in which all people enjoy all human rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments” (Amnesty International Statute). The organization also runs several campaigns to enforce international laws and standards. Its actions focus mainly on the rights of women, children, minorities and indigenous peoples, at the end of the torture, the abolition of the death penalty, refugee rights and protection of human dignity. The organization’s activity and influence increased rapidly, gaining a place in important intergovernmental organizations: it achieved consultative status by the United Nations and held a place in the Council of Europe and UNESCO before the late 1970s. In 1977, the organization received the Nobel Peace Prize and, in 1978, the United Nations Human Rights Prize. It currently has more than seven million members worldwide.

References

Amnesty International Official Site https://www.amnesty.org/en/

Hopgood, Stephen (2006), Keepers of the Flame: Understanding Amnesty International, New York, Cornell University Press.

Clark, Ann Marie (2010), Diplomacy of Conscience: Amnesty International and Changing Human Rights Norms, Oxford, Princeton University Press.

The Interkerkelijk Vredesberaad (IKV) or Interchurch Peace Council is an organization founded in November 1967 by nine Dutch churches. Striving for peace during the Cold War, the organization started by organizing a yearly ‘Vredesweek’ or Week of Peace, as well as distributing a ‘Vredeskrant’ or Newspaper of Peace. While it was initially mainly known among members of the participating churches, the organization gained national and later international attention through its efforts for nuclear disarmament. Starting in the Week of Peace of 1977, the IKV launched a campaign with the following slogan: ‘’Help rid the world of nuclear weapons, beginning with the Netherlands’’. This slogan and campaign found fertile ground in the Netherlands, and thus grew rapidly. Soon, there were over 400 local groups working towards the same goal. While the brunt of the activists were members of the churches which were involved in the organization, soon universities and newspapers joined as well. Through reports on nuclear weapons stored in the Netherlands, the population was educated on what was going on within the country. Slowly, the first steps towards internationalization of the movement were made in the late 1970s. When the NATO announced the fabrication of new cruise missiles with nuclear warheads, some of which were to be stationed in the Netherlands, the movement gained even more popularity. This popularity culminated in two mass protests: the first one was in Amsterdam in 1981, where more than 420.000 people attended. This kickstarted the internationalization of the movement, and the International Peace Communication and Coordination Center (IPCC) was founded with the IKV as leader of this group. Two years later another mass protest, this time in the Hague, attracted 550.000 people. While the IKV’s work was not very successful in the sense that the placement of nuclear warheads in the Netherlands was not prevented by its actions, the organization sparked an international movement for nuclear disarmament. After the end of the Cold War, the IKV focused its efforts on peace on a project basis. Starting with the war in Yugoslavia, the IKV continues to promote peace around the world to this day.

References

Founded in 1970 by Valery Chalidze, Andrei Sakharov, and Andrey Tverdokhlebov. The Committee on Human Rights in the USSR aimed to assist government agencies in establishing and applying human rights guarantees; research on the theoretical aspects of the human rights; and promote legal education for the public, including the publication of international and Soviet human rights documents. The Committee opposed secret trials and the death penalty. It was the first independent association in the Soviet Union to be a member of an international organization: in June 1971, it became an affiliate of the International League for Human Rights, a non-governmental organization with consultative status with the United Nations. It also became a member of the Institute of International Law. The Committee’s activities have declined since 1972, due to constant KGB surveillance, which included compromising Chalidze’s reputation, depriving him of Soviet citizenship and inciting disagreements and dissensions among Committee members and supporters, which led to Tverdokhlebov’s resignation.

References

“Committee for Human Rights in USSR, 4 November 1970”, in https://chronicle-of-current-events.com/2014/08/07/17-4-the-committee-for-human-rights-in-the-ussr/

Szymanski, Albert (1984), Human Rights in the Soviet Union, London, Zed Books.

Horvath, Robert (2005), The legacy of Soviet Dissent: Dissidents, Democratisation and Radical Nationalism in Russia, London, Routledge Curzon

The Committee of Concerned Scientists (CCS) is a human rights’ organization compounded of scientists, engineers and academics. This group appeared in 1972, in New York and Washington as a committee of scientists that wanted to help their Soviet counterparts, mainly the citizen USSR scientists who asked to leave the country and were denied their visa, the so-called “refusenik”. That refusal came with the argument that they knew State secrets that they could share with their foreign colleagues. Many of them lost their jobs at research centers and universities and were prevented from attending conferences in the scientific field. Some of these academics were deprived of their titles and forced to work in forced labor camps.

Among the different works that the Committee organized to assist these scientists, one of the most striking examples was the Science Frontiers Conference. The Committee sponsored this conference in Moscow, in 1988. It took place in the private apartments of the scientists who have been refused to leave the country. Thus, these authors were able to present their researches, as they could not participate in international meetings.

Although this group started working more directly with scientists from Eastern Europe, its work quickly evolved into other fields and found human rights’ violations in more than seventy-five countries, such as refusals of travel to scientists in Israel, the arrest of teachers in China and the violence against students in Ethiopia.

CCS promotes academic freedom and the right of scientists to collaborate in research and share data, to travel between conferences and meetings and to emigrate, if they wish so. More broadly, it deals with the defense of human rights.

References

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was created in the 1970s, following the Helsinki Agreements. It aimed to improve the relationship between the Soviet bloc and the NATO bloc. The United States, the Soviet Union, Canada, Turkey and all the European countries, excluding Albania and Andorra, met between July 3rd, 1973 and August 1st, 1975, in a set of three sessions, where it was agreed deepening cooperation on security issues. From November 1990, with the Charter of Paris, and after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the CSCE began to have permanent administrative institutions in order to allow the continuity of its work in democracy, peace and human rights, in Europe. Public consultations are also held every two years between the heads of state and government; an annual meeting of a Formal Council made up of Foreign Ministers and a regular meeting of high-level officials from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, in the form of a Committee. During the Budapest Summit in December 1994, the Conference was extended to an Organization, thus creating the “Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)”, with headquarters and permanent institutions from January 1st, 1995. The OSCE is a regional organization, headquartered in Vienna, Austria, and made up of 57 member states, including the entire European Union, the Russian Federation, Central Asian countries and North America. The purpose of this Organization is to promote democracy and human rights, as well as prevention, conflict resolution and cooperation in terms of security.

References

Created in 1976, to ensure compliance with the Helsinki Accords, and to report human rights violations in the Soviet Union to the West, the Moscow Helsinki Group is one of Russia’s leading human rights organizations. Relevant names in the fight for human rights assumed their presidency: Yuri Orlov, Larisa Bogoraz, Kronid Lyubarsky and Lyudmila Alexeyeva. Throughout the 1970s, the Group led to the formation of similar groups in other countries such as Ukraine, Lithuania, Georgia and Armenia, and even in the United States. The Helsinki Group carried out reports on the violations found and requested the intervention of the other signatory states. The reports carried out focused on several subjects, including national self-determination, emigration, freedom of belief, the right to a fair trial and the rights of political prisoners. The dissemination of ideas and news about the group was carried out by western radio stations such as Voice of America and Radio Liberty and through periodicals such as Cahiers du Samizdat and Boletim Samizdat. This spread contributed significantly to raising awareness across the Soviet Union about the issue of human rights. Consequently, members of the Moscow Helsinki Group were threatened by the KGB, arrested, exiled or forced to emigrate. The dissolution of the Moscow Helsinki Group was officially announced on 8 September 1982. Only in July 1989, the Moscow Helsinki Group was reinstated with President Larisa Bogoraz, succeeded in 1994 by Kronid Lubarsky.

References

Snyder, Sarah (2011), “Even in a Yakutian Village: Helsinki Monitoring in Moscow and Beyond”, Human Rights Activism and The End of the Cold War: A Transnational History of the Helsinki Network, New York, Cambridge University Press, pp. 53–80.

Hill, Dilys (ed.). (1989), Human Rights and Foreign Policy: Principles and Practice, New York, Macmillan.

Thomas, Daniel (2001), The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights, and the Demise of Communism, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

One of the first human rights movements in the Soviet Union was the Komitet Obrony Robotników (KOR) or Worker’s Defence Committee in Poland. After the Polish government announced steep price rises, particularly on foodstuffs, protests and riots broke out in various Polish cities in 1976. While the Polish government did recall those price rises, the protests were also very heavily suppressed. Many participating workers lost their jobs, were sent to the hospital with severe injuries or even to prison with sentences of up to 10 years. In September 1976, Antoni Macierewicz and Piotr Naimski started the KOR as a reaction to this injustice. Through the help of friendly lawyers, they tried to gain amnesty for the arrested workers, as well as trying to get fired workers their jobs back. In this process, they also assisted the workers families with money, legal counsel, and mental support. At the same time, the KOR ran a public awareness campaign. While the government newspapers described the protests as hooligan riots, the KOR smuggled printing equipment into the country and started to disseminate its own information, showing the Polish people another side to the story. Just like with the initial protests, the Polish government suppressed the KOR heavily, yet still gave in to its demands. So, while they severely harassed KOR’s members, allegedly even killing a student affiliated with the group, the government did grant mass amnesty to workers in 1977. It was at this point, one year after its original inception, that the groups initial mission of justice for the workers was complete. However, this did not mean they would stop their activism. They changed into the Komitet Samoobrony Społecznej KOR (KSSKOR) or Social Self-Defense Committee KOR. With this name-change, they morphed into a movement comparable to the various Helsinki groups of the time, and indeed worked together with the Helsinki Watch and the Swedish and Norwegian Helsinki groups. In catholic Poland, they battled suppression of human and civil rights such as religious oppression by the atheist Soviet Union administration. The KOR and subsequently the KSSKOR were very influential not only in securing amnesty, but also in showing the Polish people that dissidence was possible and effective. Soon, other groups started forming and KSSKOR was finally absorbed into Solidarnosc in the early 1980s.

References

In 1968, the Czechoslovak government intended to implement some reforms to humanize socialism, however, the Soviet Union felt threatened and invaded Czechoslovakia in August 1968, putting an end to socialist reforms known as the “Prague Spring”. In January 1977, a group of Czechoslovak intellectuals, feeling unhappy, signed a document known as “Charter 77”, which criticized the government for the failure of socialist reforms, namely the implementation of the human rights clauses in the Czech Constitution, the Final Act of the Helsinki 1975 and the United Nations’ intentions on political, civil, cultural and economic rights. 243 individuals signed the “Charter 77” and, over the next decade, more 1621 people joined the group. This document was signed by artists, writers and intellectuals, who were not satisfied with the state of the country, and defended the decentralization of the economy, the end of restrictions on presses’ freedom and expression. They called themselves a free association, without statutes or permanent bodies and without any political or opposition basis. Vaclav Havel, the former President of Czechoslovakia, was one of the “Charter 77” signatories, and one of its co-authors, as well as its spokesman when the movement was established in January 1977. Some important names in the movement included Jiri Dienstbier, who became Minister of Foreign Affairs, or writers as Ludvik Vaculik and Pavel Kohout. The “Charter 77” movement was one of the oldest human rights movements in Eastern Europe. Its signatories were constantly subject to redundancies, the refusal of access to their children’s education, the withdrawal of driving licenses, the forced exile and the loss of the citizenship. They were also victim of police harassment, arrest and trial.

References

The Christian Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Believers in the USSR was founded in 1977 by Orthodox Father GJeb Yakunin, Boris Khaibulin and Viktor Kapitanchuk. The purpose of the committee was to defend the rights of the faithful from illegal acts by the atheist state. The committee studied the legal aspects of the existence of religious groups and individual believers in the USSR. Receiving several letters from the faithful, with information on the violation of human rights, the Committee made a set of reports forwarded to the competent state agency, together with the request for the illegal activity to be stopped. When the authorities refuse to take the necessary measures, the Committee made public the injustices through reports published in the West and in the Chronicle of Current Events published in the USSR. During the period of its existence, the Soviet authorities not only ignored the Committee’s appeals, but repressed its members not in judicial ways but by means of pressure: frequently followed, victimized at work, interrogated, threatened, and having their homes searched. Gleb Yakunin was arrested and sentenced to five years of internal exile.

References

Shcheglov, V. (1983), “The Christian Committee For the Defense of Believers’ Rights in the USSR”, Religion in Communist Lands, 11(3), pp. 332–334.

Peris Daniel (1998), Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless, New York, Cornell University Press.

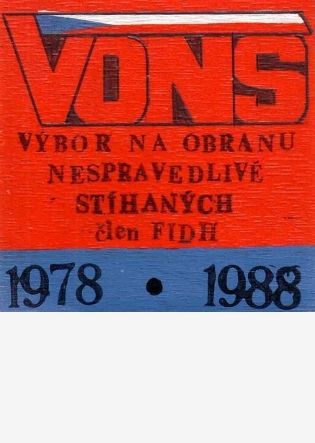

The ‘’Výbor na obranu nespravedlivě stíhaných’’ (VONS) or the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Prosecuted was founded in Czechoslovakia in April 1978. Founded by several signatories of the Charter 77, the VONS was modeled after the Polish KOR movement. Like the KOR, it sought to assist persons being persecuted by the government for their beliefs. It provided legal counsel, financial assistance, and other forms of support to these people. Next to the support provided, they also tried to raise awareness for the cases they were looking at. They did this by writing communiqués which were published in the Charter 77 newsletter, and often also broadcast by radio stations based abroad which could reach into Soviet territory. These communiqués were very important as they broke the information monopoly held by the state. Through showing the Czechoslovak people details of individual cases, the broader pattern of lies by the government was uncovered. As one can imagine, the government and secret police were not amused by these efforts, and soon many of the founding members of VONS were in prison. Others were forced to emigrate. However, their fellow dissidents were not discouraged and managed to publish a total of 1.295 communiqués between 1978 and 1989. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Velvet Revolution, VONS continued as a movement advocating for certain legal amendments in the criminal code and rehabilitation laws. It was disbanded in 1996.

References

This non-governmental organization entitled Human Rights Watch was established in 1978 with the creation of the group “Helsinki Watch”, with Robert L. Bernstein as one of the main leaders. It was set up to support citizen groups formed throughout the Soviet bloc and to verify the government’s compliance with the 1975 Helsinki Agreements.

“Helsinki Watch” had the primary intention of publicly “naming and shaming” abusive governments using media coverage and direct exchanges with lawmakers. By highlighting the international spotlight on human rights violations in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the “Helsinki Watch” contributed to the democratic transformations of the late 1980s.

“Americas Watch” was founded in 1981 and it served to prove abuses by government forces in Central America, as well as to investigate and expose war crimes committed by rebel groups, based on international humanitarian law. During the 1980s, Asia Watch (1985), Africa Watch (1988) and Middle East Watch (1989) joined “Americas Watch” starting a group known as “The Watch Committees”. In 1988, the organization formally adopted the more comprehensive name “Human Rights Watch”, which is based in New York.

Currently, this international non-governmental organization defends and conducts research on human rights in its various aspects. Its focuses on human rights’ issues extends to the rights of women and children, refugees and migrant workers. It works on issues such as domestic violence and sexual discrimination, torture and trafficking, as well as rape as a war crime and political corruption. Basically, it deals with the most diverse violations of international humanitarian law.

References

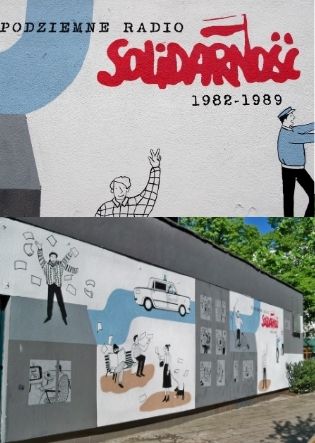

“Solidarity” is the English word for “Solidarność”, which was the first independent union in a Soviet bloc country. More specifically, on September 22nd, in 1980, Solidarność was formally founded when 36 regional unions joined together. This union came about after a strike led by Lech Walesa, which started in August 1980. This strike brought together workers from the Lenin Shipyards, in Gdansk. Workers demanded salary increase and the readmission of dismissed colleagues. Following this first strike, some others extended across the country, which led the strikers and the government to an agreement that allowed free and independent unions, with freedom of political and religious expression. In early 1981, the union had about 10 million people and represented the majority of Poland’s workforce. Throughout that year, Solidarność became increasingly strong and participative in society, carrying out several strikes that called, mainly, for economic reforms and free elections. During this period, the union’s positions hardened, and the Polish government was subjected to pressure from the Soviet Union to suppress it. The union was even declared illegal and its leaders were arrested. Solidarity was dissolved by Parliament in October 1982 and went underground. In 1988, strikes returned to Poland and the strikers intended the government to once again recognize the Solidarność union, which was again legalized in April of that year, having participated in free elections for Parliament. After winning seats in Parliament, they formed a coalition government with PUWP, under the leadership of Tadeusz Mazowiecki. However, after disagreements between Mazowiecki and Lech Walesa, the latter became President of Poland in 1990. This division between the two leaders prevented the formation of a coalition supported by Solidarity to govern the country and the role of the union became weaker as new political parties emerged in the early 1990s.

References

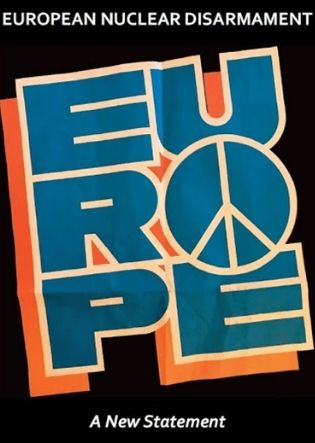

European Nuclear Disarmament (END) was established in the United Kingdom in 1980. And it had Mary Kaldor as one of its founders members. This group has closely linked itself to other groups in Eastern Europe. However, many similar movements were born in France, Germany or the United States, during the Cold War, against nuclear proliferation.

After months of work and preparation, an appeal for European nuclear disarmament was launched in the House of Commons. This document was produced by E.P. Thompson, with the collaboration of other personalities, such as Mary Kaldor, Ken Coates and Robin Cook. It demanded an Europe that was not aligned and without nuclear weapons, from “Poland to Portugal”.

References

http://www.russfound.org/END/EuropeanNuclearDisarmament.html

Founded in 1982, the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights was a non-governmental and non-profit organization. The Federation had the specific objective of ensuring compliance with the human rights provisions of the Helsinki Final Act together with the countries that adopted it and providing an organization on which the various independent committees could appeal if they had questions. Gathering and analyzing information on human rights conditions in OSCE countries, it disseminated them to governments, intergovernmental organizations, the press and the general public. The Federation established contact with individuals and groups that defended human rights in countries that did not adopt the Helsinki Convention. The Helsinki International Federation for Human Rights received the European Human Rights Award in 1989.

References

“International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights (IHF)” https://www.ecoi.net/en/source/11257.html

Snyder, Sarah (2011), Human Rights Activism and The End of the Cold War: A Transnational History of the Helsinki Network, New York, Cambridge University Press.

The Campaign for Peace and Democracy was established in 1982, in New York City, and promoted a non-militaristic foreign policy for the United States, while collaborating with social justice movements. This organization opposed the Cold War, calling for a “détente from below”. It involved Western activists in defense of the democratic dissidents’ rights in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and enlisted human rights activists from the Eastern bloc against US anti-democratic policies in countries like Nicaragua and Chile.

Currently, this organization defends the existence of a new non-militaristic foreign policy by the United States, which encourages democracy and social justice, promoting peace movements and activists around the world. It opposes the existing American foreign policy, which is based on domination and militarism and support for authoritarian regimes. Many Americans argue that their country’s foreign policy, mainly the so-called “War of Terror”, serves to strengthen dictatorships or terrorism, around the world.

References

Founded on 24 January 1986, The Initiative for Peace and Human Rights was the oldest opposition group in East Germany, independent of the churches and the state. In the beginning, it had an organizational structure that had only about 30 members. The people involved in the Initiative included Bärbel Bohley, Werner Fischer, Peter Grimm, Ralf Hirsch, Gerd Poppe, Ulrike Poppe, Martin Böttger, Wolfgang Templin and Ibrahim Böhme. The Initiative campaigned for disarmament and demilitarization and condemned any type of authoritarian structure, violence and the exclusion of minorities and foreigners. In January 1988, several members of the Initiative were arrested and later deported to the West. In November 1988, when Romanian leader Nicolae Ceaușescu was invited to visit East Germany, civil rights activists organized a Romanian evening at the Church of Gethsemane in East Berlin to draw attention to the violation of fundamental rights in Romania. Subsequently, several members of the Iniciative were placed under house arrest during Ceauşescu’s visit. On 11 March 1989, it became the first opposition group to expand across East Germany.

References

“Initiatives For Peace And Human Rights” in https://www.iphr-ipdh.org/who-we-are.html