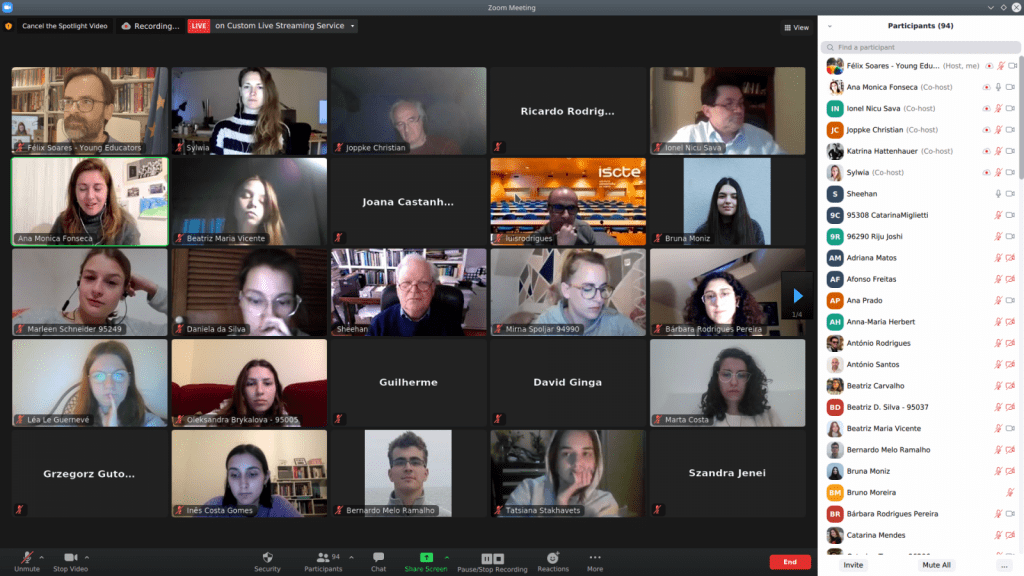

The webinar “Peaceful revolution as a social resistance movements: The Unknon Citizens and the Fall of the Wall” was moderated by professor Ana Mónica Fonseca, from Iscte-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa and took place on March 8th, 2021. This webinar featured Professor Christian Joppke, from University of Bern, Katrin Hattenhaeur, human rights activist, Professor James Sheenan, from University of Stanford, and Professor Ionel Nava, from University of Bucharest. The NoWall project, which includes this webinar, is funded by the European Commission and is supported by several partners, including the European Association of Young Educators.

Christian Joppke is a German political sociologist, author of several publications about citizenship and emigration. “East Germany’s unhappy dissidents” was the motto of his participation. Joppke opened the presentation explaining why opposition in democratic Germany was so different and in what terms it took place. The professor intends to take a look at the social movements in communist regimes, so he started by approaching Leninism, characterizing it as a combat regime, which, due to its characteristics, is transformed into activism. Then, Joppke returns to the term “dissident”, explaining that it is the most correct way to express opposition to a regime. In this case, East German dissidents were different from everyone else as they remained loyal to what they opposed. Democratic Germany was the home of intellectuals, the republic of letters, so the researcher considers that these dissidents practiced an intellectual opposition. Later, they were called fighters against the dictatorship, a term never used in the 1980s to define the communist regime in democratic Germany.

Then, the human rights activist, Katrin Hattenhauer, shared her personal experience. She had no plans to become an activist. However, from an early age, she joined an ecological movement that planted trees. She realized that she could not apply to college because she was against the regime so she moved to Leipzig where she ended up studying at a Protestant university. Katrin asks why did the peaceful revolution start in Leipzig and not not in Berlin? She answered the same question by specifying that there was a younger generation in Leipzig who understood the need to fight against the regime. This activist recalls the group to which she belonged and where she was the last to join, sharing that there were only 12 members and they worked secretly. Only members who would have risked their lives and hadn’t betrayed others, were accepted. It should be noted that most of the questions after the presentations were addressed to Katrin due to the curiosity about the themes that she had explored during her presentation.

The third speaker, Professor James Sheehan, headed the topic “The problem of peaceful change: What are the conditions necessary to make a revolution peaceful? What role did the social movements in East Germany play in this process?”. Sheenan says that he was part of history, in the 1980s, as a spectator and, later, as a historian. He questioned the reason why the regime did not act violently against the movements that were formed and said that he was not sure what the final result of that process would be. Sheenan wonders if this was an effort to change the regime or simply an effort to do just a few changes? The regime believed that it could survive to that changes and that it wouldn’t be a “life and death” topic. James Sheenan asks “How far the regime shoud go to defend itself?” and addressed the international context of peace and non-violence. He concluded that the price of a violent revolution is higher than that of a peaceful one.

The last speaker, Professor Ionel Sava, is a researcher in International Relations as well as a sociologist and deals with the theme “Difference between dissidents’ action in Eastern Germany and the eastern block of Polish, Czech and Hungarian anti-communists”. He stated that the 70s and the 80s are profoundly different from the previous decades and that events from a historical point of view are important to understand the transformations of this period. Sava indicated that sociologists refer to the existence of a containment policy that began in the 1970s, which lasted until the end of the 1990s, that resulted in democratization and the transition to the economic market. In the late 1980s, groups such as intellectuals, trade unions and the Catholic Church made a difference to increase the possibilities for revolutionary change. The sociologist spoke to us of a cultural identity beyond regions and borders. Many dissidents could be expelled from their countries, but they remain in contact with their comrades.

This webinar was extremely important because it brought to the debate the view of academics on the subject as well as the personal experience of a human rights activist, which enriched the subsequent discussion. The importance of values such as freedom and human rights, essential for this project, was reinforced.

Full video: