Source: Bundesarchiv, 1980

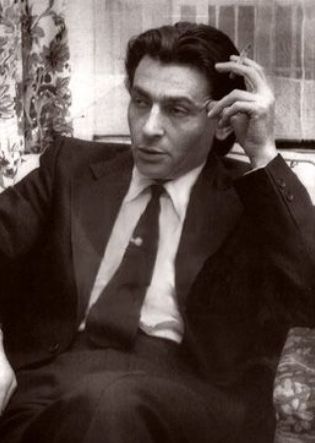

Karl Herbet Frahm, known as Willy Brandt, was born on 18th december, 1913, in northern Germany. He changed his name in the early 1930s and fled to Norway to avoid being arrested by the Nazis. After the German occupation of Norway, in 1940, he fled to Sweden where he lived until 1945, then he returned to Germany after the World War II. Willy Brandt began his political career in 1948 and held various positions within the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He was Mayor of West Berlin between 1957 and 1966. During this period, he became internationally known, at the same time, the Berlin Wall was being built. Brandt was the party’s leading figure and Chancellor candidate of the Federal Republic of Germany; However, he did not hold this role until 1969. He was Chancellor from 1969 to 1974, when he resigned due to a political scandal with one of his personal assistants who proved to be an East German spy. As a Chancellor, Willy Brandt invested on foreign policy and sought to reconcile and strengthen the relationship between West Germany and East Germany, as well as Poland and the Soviet Union, raising a policy known as “Ostpolitk”. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971 due to this work. Despite his resignation as a Chancellor, Willy Brandt remained the Party leader until 1987 and became his honorary President until his death. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in the end of 1989, Willy Brandt promoted the reunification of both parts of Germany and the union of Europe. He died after prolonged illness in October 1992.

Reference

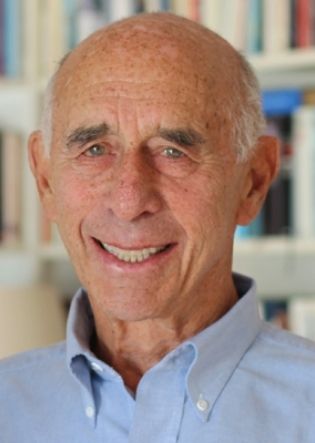

Author: Hans Schafgans, 1977

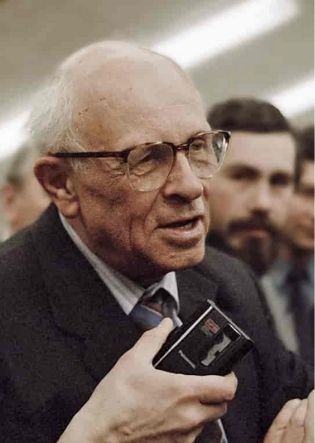

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt was born in 23rd of december, 1918, in Hamburg, Germany. He was a social democratic politician, specifically a Chancellor of West Germany between 1974 and 1982. Schmidt succeeded as a Chancellor of West Germany after the resignation of Willy Brandt. He served the German Army during World War II. After the war, in 1946, Schmidt joined the Social Democratic Party (SPD), reaching the role of Party Vice President in 1968. As a student of economics at the University of Hamburg, Schmidt worked in the sector in the city’s municipal government from 1949 to 1953 and in 1953 he was elected to the Bundestag, German parliament, where he remained until 1961. Between 1961 and 1965, he returned to Hamburg, when he was reelected to the Bundestag. He was Minister of Defense and Finance in the different governments of Chancellor Willy Brandt between 1969 and 1974. After the resignation of Willy Brandt, Helmut Schmidt was elected Chancellor of West Germany and held this role until 1982, when he resigned after losing the majority of votes in the Bundestag. His successor was Helmut Kohl, of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). During his tenure, he gained international respect, although he hadn’t the charisma of his predecessor, Willy Brandt, and didn´t benefit from the parliamentary majorities and diplomatic opportunities of his successor, Helmut Kohl. Schmidt remained a member of the Bundestag until 1986, when he retired from political life. He has written several books about German political affairs and European international relations. From 1983 until his death, Schmidt was also co-editor of “Die Zeit” newspaper. Helmut Schmidt passed away on 10th November of 2015, in Hamburg.

Reference

https://www.willy-brandt-biography.com/contemporaries/r-s/schmidt-helmut/

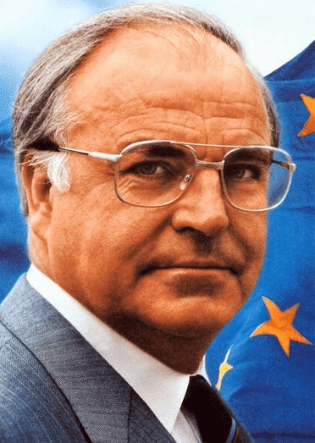

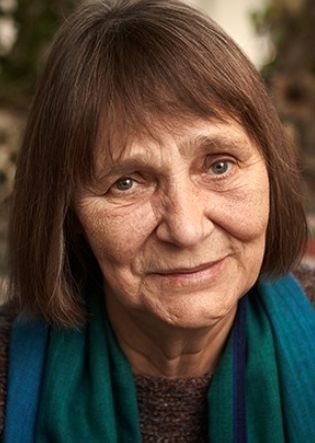

Source: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 1989

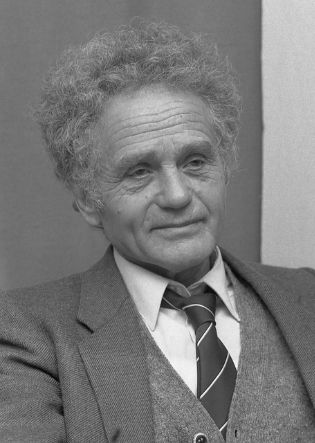

Helmut Kohl was the Chancellor of West Germany between 1982 and 1990 and he was also the first Chancellor of the unified Germany, from 1990, having remained in the role until 1998. Kohl led Germany to reunification and he also defended the euro as the single European currency. Helmut Kohl was born on April 3, 1930, in Germany, and received a PhD in Political Science at the University of Heidelberg. He became interested in politics from an early age and in 1947 he began to collaborate with a youth organization in his hometown, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Kohl was elected the Vice President of the Party in 1969 and he became President of the Party in 1973. In 1976, he was at the running for election, but he had lost that position to Helmut Schmidt of the SPD. Helmut Kohl became Chancellor of West Germany only ten years later, in 1983, through a coalition of three parties; CDU, CSU and FDP. This happened because the former Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, received a vote of no confidence in the Bundestag by his coalition partners of the government. Between 1983 and 1987, the following elections, which were also won by Kohl and the coalition of ruling parties, the policies of this Chancellor’s government focused on West Germany’s commitments to NATO. In 1989, when the Soviet Union eased its grip on East Germany, Kohl led German reunification. In October 1990, East Germany was dissolved, and its constituent states joined West Germany, reuniting the country. In December 1990 the first free and fully German parliamentary elections since 1932 took place, where Kohl and his ruling coalition CDU-CSU-FDP won a majority in the Bundestag. Helmut Kohl passed away on June 16, 2017.

References

Pruys, Karl Hugo, (1996), “Kohl: Genius of the Present: A Biography of Helmut Kohl”, Edition Q.

Clay Clemens and William E. Paterson, (Eds.), (1998), “The Kohl Chancellorship”, Londres, Routledge.

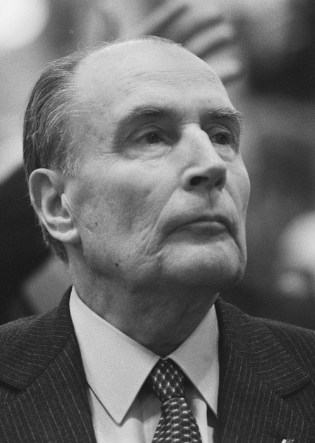

Source: Fotocollectie Anefo Reportage, 1988

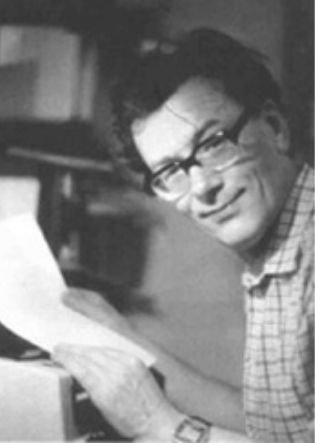

François Mitterrand was born on October 26th, in 1916, in France, and he was a French politician who served the country, as a President, for two terms. Mitterrand studied Law and Political Science, in Paris, and in 1946 he was elected to the National Assembly. The following year he became Minister of Cabinet in the coalition government of Paul Ramadier. During the years after, Mitterrand held various positions in various governments of the Fourth French Republic. Since 1958, François Mitterrand became an opposition to Charles de Gaulle, who would become President the following year. In 1965, Mitterrand ran against De Gaulle as a candidate for the French Presidency and took the election to a second round. In 1971, he was elected as the first secretary of the Socialist Party and started the party reorganization. In 1974, Mitterrand ran again for the Presidency and was defeated again. He acceded to the Presidency only in 1981, after the defeat of President Giscard d’Estaing. He was the first Socialist President of the Fifth Republic. During Mitterrand’s term of foreign policy, France developed its relationship with the United States, maintaining a tougher stance towards the Soviet Union. In 1986, Mitterrand had Jacques Chirac as the Prime Minister, in a power-sharing agreement called “Cohabitation”, however, Mitterrand maintained the country’s foreign policy. Two years later, in 1988, Mitterrand ran again for the Presidency and at the same time he started the promotion of European unity. He is one of the main defenders of the 1991 European Union Treaty, which sought a European banking system, a common currency and a unified foreign policy. His second term ended in May, 1995, with the election of Jacques Chirac. François Mitterrand died of prostate cancer, at the age of 79, less than a year after he ended his second presidential term.

References

Cole, Alistair, (1997), “Francois Mitterrand: A Study in Political Leadership”, Londres, Routledge.

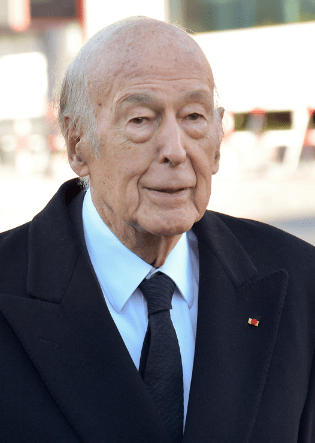

Source: Wolf Krause, 2015

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was a French politician, who served as President of the Fifth Republic of France, between 1974 and 1981.Giscard d’Estaing was born on February 2nd, in 1926 and he participated in the French Resistance during World War II. When he was 18, he joined the French Army, having been awarded with the “Croix de Guerre” due to his participation in campaigns during the World War II.This French politician studied at the Polytechnic School and the National School of Administration, and he joined General Finance Inspection, in 1952.Between 1956 and 1974, he was a deputy in the French National Assembly of Puy-de-Dôme, and he was a delegate to the General Assembly of United Nations, between 1956 and 1958. In 1962, he became Minister of Finance and Economic Affairs for President Charles de Gaulle, position which he held until 1966. Between 1969 and 1974, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was Minister of Economy and Finance of President Georges Pompidou. At the age of 48, Giscard d’Estaing was elected President of France against the candidate François Mitterrand, on May 19, 1974. During this period which lasted until 1981, the French President played an important role in the creation of European Council and european monetary system as well as the European Parliament’s universal suffrage. In 1981, Giscard d’Estaing was defeated in a second round with François Mitterrand, but returned to politics the following year as a general counsel for the department of Puy-de-Dôme, where he remained until 1988. Between 1984 and 1989, he was elected to the National Assembly of Puy-de-Dôme again, and he was re-elected in 1993 and 1997. Between 1989 and 1993, the former French President was a Member of the European Parliament and in 2001 the European Council made him President of the Convention on the Future of Europe. At the age of 94, Giscard d’Estaing is the longest-lived French President in history.

References

Roussel, Eric, (2018), “Valéry Giscard d’Estaing”, Paris, L’OBSERVATOIRE.

Bernard, Mathias, (2014), “Valéry Giscard d’Estaing: Les ambitions déçues”, Armand Colin.

Source: Bundesarchiv, 1967

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev was born in Ukraine on December 19, in 1906 and he was the leader of the Soviet Union for 18 years.

Brezhnev became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1931 and during the World War II he was a political commissioner of the Red Army. He became Major General in 1943 and led the political commissioners on the Ukrainian front. Brezhnev’s career flourished during Stalin’s regime and, in 1939, he became Secretary of the Regional Committee of the Dnepropetrovsk Party.

After the war, in 1952, Brezhnev became a member of the Party’s Central Committee and also a candidate for membership of the Politburo. However, after Stalin’s death, in 1953, Brezhnev lost his positions and it was Nikita Khrushchev who, in the following year, chose him as the second secretary of the Kazakhstan Communist Party. He became first secretary in 1955 and, a year after, he was re-elected to the same positions in the Central Committee and the Politburo.

Brezhnev succeeded Nikita Khrushchev as the leader of the Soviet Communist Party in 1964, with Aleksey Kosygin as Prime Minister. In the late 1960s, Brezhnev developed the Brezhnev Doctrine, which says the Soviet Union had the right to interfere in cases where its interests were being threatened. During the 1970s, Cold War tensions started a period known as Détente. Brezhnev became President, in the late 1970s, in 1977, through a new Constitution, becoming the first Party and State leader at the same time. He was the Secretary General of the Party for 18 years, until his death on November 10, 1982.

References

(1978), “Leonid I. Brezhnev: Pages from His Life”, Nova Iorque, Simon & Schuster.

Source: RIA Novosti archive, 1987

Mikhail Gorbachev was born on March 2, in 1931, in Russia and he was the Secretary General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, between 1985 and 1991, and the President of the Soviet Union, between 1990 and 1991. He also received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990, for his contribution to the end of the Cold War. It was with Gorbachev that the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991.

In 1952, Gorbachev got into college to study Law and, at the same time, he became a member of the Communist Party. He graduated in 1955 and he held various positions in the Communist Party Youth Organization, known as Komsomol, and in regular party organizations, becoming First Secretary of the regional Party Committee in 1970. In the following year, he was chosen as a member of the Committee Central of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In 1978, he became the Secretary of Agriculture of the Party. A year after, Gorbachev became a candidate to the Politburo and a full member the following year.

Mikhail Gorbachev was elected Secretary General of the Communist Party in 1985 and President of the Soviet Union in 1990. During his tenure, Gorbachev created policies such as Glasnost and Perestroika, which started in the late 1980s. The first intended to be a policy of open discussion of political and social issues, especially in terms of freedom of expression and information, and the second, a program to redevelop politics and economy.

In foreign policy, Gorbachev maintained close relationships with some western political leaders, such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Tatcher or Helmut Kohl. It should be noted that Gorbachev played an important role for the end of the Cold War, for the fall of the Berlin wall and for German reunification.

References

Taubman, William, (2017), “Gorbachev: His Life and Times”, Reino Unido, Simon & Schuster.

Brown, Archie, (1997), “The Gorbachev Factor”, Reino Unido, Oxford University Press.

Source: MEDEF, 2009

Lech Wałęsa was born on September 29, in 1943, in Poland. He was an activist who formed and led the first independent union in communist Poland, Solidarity. Wałęsa received the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1983, and he was the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995.

Son of a carpenter, Wałęsa received professional education and, in 1967, he started working as an electrician at the Lenin shipyard, in Gdańsk. In 1976, after protests against the Communist government in Poland, Lech Wałęsa emerged as an anti-government union activist and lost his job. On August 14, in 1980, during some protests at the shipyard, Wałęsa led a strike which started a wave of strikes across the country and communist authorities were forced to negotiate the Gdańsk Agreement with Wałęsa. This agreement gave workers the right to strike and to have an independent union.

On September 22, in 1980, Solidarity was formally founded when 36 regional unions came together and in the following year, Lech Wałęsa was elected President of the union, officially recognized by the government. When the Polish government imposed martial law, Wałęsa’s party was banned, most of its leaders were arrested, including Wałęsa, who was in jail for almost a year. The government criticized the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Wałęsa in 1983, however, he was recognized for his peaceful struggle for workers’ rights.

In 1988, the government made Solidarity a legal party that participated in free elections and won the majority of seats in the upper house of parliament. However, Wałęsa refused the post of Prime Minister, but he became President of Solidarity in April 1990. In December of the same year he was elected President of the Republic of Poland, a position he held until November 1995. That same year, Wałęsa announced he was leaving political life and he would dedicate himself to the Lech Wałęsa Institute, which aimed to promote democracy and civil society.

References

Stefoff, Rebecca, (1992), “Lech Walesa: The Road to Democracy”, (Great Lives), EUA, Ballantine Books

Walesa, Lech, (2016), “Struggle and the Triumph: An Autobiography”, Nova Iorque, Arcade Publishing

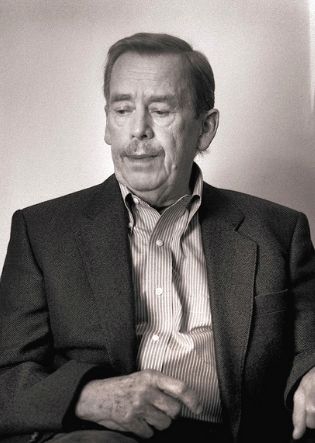

Source: Jiří Jiroutek, 2014

Vaclav Havel was born in Prague on October 5, in 1936. He was a writer, a dramatist as well as a politician of the Czech Republic. He was also an activist for human rights and he fought for the freedom of expression since the Prague Spring, in 1968. After the communism falling, Vaclav Havel became the president of Czechoslovakia between 1989 and 1992 and the Czech Republic between 1993 and 2003.

Havel began his career at a theater company in Prague, in 1959, where he began to write plays, and he became a residente dramatist at the Balustrade theatre company in the late 1960s. Havel was an active participant in the Prague Spring, in 1968. After that, his plays were censored. Between the 1970s and 1980s, Havel was in jail for several periods because of his activities defending the human rights, including an arrest of four years, between 1979 and 1983. In January 1977, people knew about “Letter 77”. Vaclav Havel was one of the signatories, co-authors, as well as spokesperson, of that document.

With the end of the communist regime, Havel was named President of the Republic, a position he had held between 1989 and 1992. However, the country became divided with the declaration of Slovakia’s Independence and Havel resigned. In January 1993, Havel returned to the Presidency, having been elected by Parliament. During his presidency, between 1993 and 1998, Havel was involved in strengthening civil society and giving help to some Central European countries to became part of NATO as well as part of the European Union. Havel defended the minorities’ rights and he was against the influence of political parties on society and economy.

Havel, the country’s first President after the Velvet Revolution, passed away on December 18, 2011, at the age of 75.

References

Zantovsky, Michael, (2014), “Havel: A Life, Londres, Atlantic Books.

Havel, Vaclav, (2008), “To the Castle and Back”, Nova Iorque, Vintage.

Keane, John, (2001), “Vaclav Havel: A Political Tragedy In Six Acts”, Nova Iorque, Perseus.

Valery Chalidze was a theoretical physicist who, alongside with the Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov, campaigned to expose human rights violations in the Soviet Union.

Valery Nikolayevich Chalidze was born in Moscow on the 25th November, 1938. He studied physics at Moscow State University and graduated in 1958. In 1965, the physicist received the equivalent of a PhD in Physics from Tbilisi State University in Georgia. He was the head of a physics laboratory when he became a dissident. Chalidze founded an underground newspaper, entitled “Social Issues” and defended the Jews’ rights to whom were denied emigration from the Soviet Union, and wrote the first document on the subject. Chalidze specialized in repairing typewriters, essential to disseminate prohibited literature in the country (samizdat).

In 1970, Chalidze, together with Sakharov and Andrei Tverdokhlebov, founded the Human Rights Committee in the USSR, one of the first human rights organizations in the Soviet Union.

Chalidze was one of the main activists in the defense of homossexuals’ rights in the Soviet Union. He suffered reprisals from Soviet authorities, who persecuted him, searched his apartment and launched rumors about his sexuality.

In 1972, while Chalidze was in the United States speaking at conferences and forums on human rights, the Soviet government revoked his citizenship. Thus, Chalidze remained in the country and he became an american citizen in 1979.

Chalidze continued his activism in exile, writing books on Soviet political and legal life. He also edited a bimonthly publication “A Chronicle of Rights Human in USSR”, which pointed out arrests and intimidation acts against Soviet political dissidents. The physicist was responsible for launching the publishers Khronika Press and Chalidze Publications, which published classics of literature in Russian and translations of works of history and philosophy.

The physicist settled in Vermont in 1983 and taught at Yale University, however, he has been a visiting professor at other colleges and, in recent years, he has written books on human rights, physics and other topics.

Chalidze passed away in the United States on January 3rd, 2018, at the age of 79.

Source: Vladimir Fedorenko, 1989

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov was a Soviet nuclear theoretical physicist who was born on the 21st May, 1921, in Moscow. Sakharov received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 as an international recognition in the defense of human rights, freedoms and reforms in the Soviet Union.

Andrei Sakharov graduated from the Moscow University Faculty of Physics in 1942 and worked as a scientist until 1945. Then, he started his doctorate at the Lebedev Institute, in the Physics department of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Igor E. Tamm, a renowned theoretical physicist, was his teacher. The physicist’s PhD thesis was about nuclear energy and he was included in a research group working on the development of nuclear weapons. During this period, Sakharov and Igor Tamm made a proposal that led to the construction of the hydrogen bomb.

Sakharov was rewarded by becoming a full member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, when he was just 32, with privileges from the Nomenklatura, the name given to the Soviet Union’s elite membership. During the 1960s, the physicist published an article “Progress, Peaceful Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom”. This article was responsible for his expulsion from the working group and he was deprived of his privileges. Then, he became an assistant professor, at the Lebedev Institute. A decade later, Sakharov, together with Chalidze and Tverdokhlebov, founded the Human Rights Committee in the USSR, to defend human rights and victims of political trials.

He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 for defending human rights and for trying to bring the Soviet Union closer to other non-communist nations. He was not allowed to receive it personally. Sakharov continued his work on the subject of Human Rights and, in the early 1980s he was exiled to Gorky with his wife, Yelena Bonner. Only after Mikhail Gorbachev got into power, in 1986, they were allowed to return to Moscow.

In March 1989, the physicist was elected to the First Congress of Popular Deputies, representing the Academy of Sciences. Sakharov saw many of his causes became official policies of Gorbachev and his successors. He died in Moscow on December 14, 1989.

References

Gorelik, Gennady and Antonina Bouis, (2005), “The World of Andrei Sakharov: A Russian Physicist’s Path to Freedom”, Oxford, Oxford University Press

https://www.amazon.com/World-Andrei-Sakharov-Russian-Physicists/dp/019515620X

Lourie, Richard, (2002), “Sakharov: A Biography”, Brandeis University Press

https://www.amazon.com/Sakharov-Biography-Richard-Lourie/dp/1584652071

Sidney D. Drell and George P. Shultz (Editors), (2015), “Andrei Sakharov: The Conscience of Humanity”, Hoover Institution Press Publication

https://www.amazon.com/Andrei-Sakharov-Conscience-Institution-Publication/dp/0817918957

Born on 30 September 1940 in Moscow, Andrei Nikolayevich Tverdokhlebov was a Soviet physicist, dissident and human rights activist, graduated from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. In 1970, he founded the USSR Human Rights Committee with Valery Chalidze and Andrei Sakharov and was also one of the founders of Group 73, a human rights organization that helped political prisoners in the Soviet Union. In 1974, Tverdokhlebov was approached by KGB agents, who searched his apartment and inspected various items, including documents defending civil rights; address books of political prisoners and their families; address books of German families wishing to emigrate to the Federal Republic of Germany and materials on the situation in labor camps and prisons. On 18 April 1975, Tverdokhlebov was arrested and taken to Lefortovo prison, and in April 1976 he was sentenced by the Moscow Municipal Court to five years of exile for spreading ideals that discredited the Soviet state. In 1980, he emigrated to the United States, where he continued his scientific research at Lehigh University and later at Drexel University, where he received his doctorate in 1989. He died at the age of 71 on 3 December 2011 in Pennsylvania.

References

“The Arrest of Andrei Tverdokhlebov” in https://chronicle-of-current-events.com/2019/06/29/the-arrest-of-andrei-tverdokhlebov-18-april-1975-36-1/

Horvath, Robert (2005), The Legacy of Soviet Dissent: Dissidents, Democratisation and Radical Nationalism in Russia, London, Routledge Curzon.

Source: Rob C. Croes, 1986

Yuri Fyodorovich Orlov was born on 13 August 1924 and was a physicist, human rights activist and Soviet dissident. In 1952, he graduated from Moscow State University and began his postgraduate studies at the Institute of Theoretical and Experimental Physics and obtained the title of Candidate in Science in 1958 and the title of Doctor of Science in 1963. In May 1976, he organized the Moscow Helsinki Group and became its president, systematically documenting the Soviet human rights violations defined in the Helsinki agreements. Orlov ignored the KGB’s orders to dissolve the Group and was arrested in February 1977 and sentenced to seven years of forced labor and five years of internal exile for his work. On 30 September 1986, the KGB proposed to expel Orlov from the Soviet Union and withdraw his Soviet citizenship, which was approved by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In 1990 alone, Gorbachev restored Soviet citizenship to Orlov and 23 other prominent exiles and emigrants who lost their rights between 1966 and 1988. In 1995, the American Physical Society awarded him the Nicholson Medal for Humanitarian Service. Orlov died in September 2020.

References

“Remembering Yuri Orlov” in https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/02/remembering-yuri-orlov

De Boer, S. P.; Evert Driessen; Hendrik Verhaar (1982), “Orlov, Jurij Fedorovič”. Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in The Soviet Union: 1956–1975, Leiden, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, pp. 405–406.

Orlov, Yuri, Thomas P. Whitney (1991), Dangerous Thoughts: Memoirs of a Russian Life Hardcover, New York, William Morrow & Co.

Source: European Union – EP

Jiri Pelikan was born on 7 February 1927 in Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. Pelikan became a member of the Communist Party while still studying at the University of Social and Political Sciences in Prague. With the communist coup in 1948, he became president of the Czechoslovak student union and later worked for the KSC Central Committee, becoming a deputy in the National Assembly. In 1970 he lost his citizenship and seven years later became an Italian citizen.

Editorial activities, like the publication of Listy – a magazine for exiles –, his contact with events in Czechoslovakia, as well as his adhesion to the group Carta 77, drew the attention of the Czech-Slovak secret police. As a result, in 1975, he was the target of an abduction attempt when he made a clandestine visit to Czechoslovakia.

Pelikan represented Italian Socialists as a deputy in the European Parliament between 1977 and 1989. After the 1989 “Velvet Revolution”, Pelikan became director of the East West Institute in Rome, and in 1990-91 served in the advisory council of President Vaclav Havel.

References

https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/jun/30/guardianobituaries.kateconnolly

Pelikán, Jiří (1976), Socialist Opposition in Eastern Europe: The Czechoslovak Example, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Pierre Kende was born in Budapest on 26 December 1927. He first studied Law, and then History and Sociology at the Pázmány Péter Catholic University in Budapest.

Kende joined the Hungarian Communist Party, and in March 1947 joined the party newspaper staff – Szabad Nép (Free People) –, later becoming its foreign editor-in-chief. After attacking the party’s editors and leadership policy at a party meeting in October 1954, he was dismissed by Szabad Nép. When the revolution broke out, Kende became editor of the newspaper Magyar Szabadság (Hugarian Freedom). From November to December 1956, he worked alongside Miklós Gimes as editor of the unlawful opposition newspaper Október Huszonharmadika (October 23).

He left Hungary in January 1957 to escape the wave of arrests and settled in Paris, where he obtained a PhD in Sociology. In Paris, he published many books and articles about socialism in Eastern Europe.

Kende was a member of the team at the Imre Nagy Institute in Brussels between 1959 and 1964, and in 1978 he founded the newspaper Magyar Füzetek (Hungarian Pamphlets), which he edited until 1989. In 1983, he was nominated Vice-President of the Hungarian League of Human Rights. Since 1993 he has been a professor at the Loránd Eötvös University and the Századveg School of Politics in Budapest. Kende is an international member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and a member of the 1956 Institute.

References

http://www.rev.hu/history_of_56/szerviz/kislex/biograf/kende.htm

Larisa Iosifovna Bogoraz was born on 8 August 1929 and was a dissident in the Soviet Union. On 25 August 1968, it organized a demonstration, along with Pavel Litvinov, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, Vadim Delaunay and other demonstrators in Red Square against the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia. All participants were arrested and Bogoraz was sentenced to four years of exile in Siberia. Soon after her release, Bogoraz resumed her resistance to the Soviet regime, highlighting in 1975 a letter to Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB at the time, asking him to open the organization’s archives and in 1986 a campaign to free all political prisoners. The campaign was successful because, the following year, Secretary-General Mikhail Gorbachev began to release them. In 1989, Bogoraz joined the Moscow Helsinki Group, of which she would be president between 1989 and 1994. Even after the end of the Soviet Union, she continued her activism, holding seminars on the defence of human rights, becoming president of the Seminar on Human Rights, a Russian-American non-governmental organization. She died on 6 April 2004, aged 74.

References

Vaissié, Cécile (2008), Russie, Une Femme en Dissidence : Larissa Bogoraz, Paris, Plon.

Reddaway, Peter (2020), The Dissidents: A Memoir of Working with the Resistance in Russia, 1960-1990, Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press.

Born in the city of Pskov, on 4 April 1934, Kronid Arkadyevich Lyubarsky, was a journalist, dissident, human rights activist and Russian political prisoner. In the mid-1960s, Lyubarsky became active in the civil rights movement and became a collaborative editor for several publications, including the Chronicle of Current Events (April 1968 and August 1983), documenting, arrests, lawsuits, incarceration in psychiatric hospitals and other forms of harassment in the Soviet Union. In 1972, Lyubarsky was arrested and spent five years in various forced labor camps and prisons in Mordovia, as well as in Vladimir Central Prison. Deprived of his citizenship, he sought political asylum in West Germany. In Munich, Lyubarsky founded a newsletter, Vesti iz SSSR, (1978-1991) on the human rights situation and resistance to the communist regime in the Soviet Union. Lyubarsky returned to Russia after the dissolution of the USSR and his citizenship was restored in June 1992. He was one of the authors of the current Constitution of the Russian Federation, writing many of the articles on the right to freedom of movement and residence on Russia’s borders. From 1993 to 1996, Lyubarsky led the Moscow Helsinki Group. Lyubarsky died of a heart attack on 23 May 1996, at the age of 61.

References

“The Trial of Kronid Lyubarsky” in https://chronicle-of-current-events.com/2016/11/05/the-trial-of-kronid-lyubarsky-october-1972-28-4/

Source: Vitaliy Ragulin, 2011

Lyudmila Mikhaylovna Alexeyeva was born on 20 July 1927 and was a Russian historian and human rights activist. From 1968 to 1972, she worked clandestinely in the bulletin The Chronicle of Current Events, dedicated to human rights violations in the USSR. In February 1977, Alexeyeva fled the USSR to the United States after an offensive against members of The Chronicle by Soviet authorities. Even in the United States, Alexeyeva continued to advocate for the improvement of human rights in Russia and worked for Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty and Voice of America. She regularly wrote about the Soviet dissident movement for publications in English and Russian. In 1993, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, she returned to Russia and became president of the Moscow Helsinki Group in 1996. Alexeyeva accused the Russian government of numerous human rights violations, including regular prohibitions on meetings and encouraging nationalist policies. Since 31 August 2009, Alexeyeva has been an active participant in Strategy-31, which consists of regular citizen protests in Moscow’s Triumfalnaya Square in defence of Article 31 (On Freedom of Assembly) of the Russian Constitution. She was eventually arrested on 31 December 2009, during one of these protest attempts, by the riot police. She died in Moscow on 8 December 2018.

References

“Remembering Lyudmila Alexeyeva, the Matriarch of Russia’s Human Rights Movement” in https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/12/11/remembering-lyudmila-alexeyeva-matriarch-russias-human-rights-movement

Alexeyeva, Ludmilla; Paul Goldberg (1990), The Thaw Generation: Coming of Age in the Post-Stalin Era, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Source: Civil Rights Defenders

Hans Gerald Nagler, was born on December 10, 1929 in Vienna, is an Austrian-Swedish businessman and human rights activist.

During his career, integrated into different organizations, he defended the raising of awareness about human rights violations. As a co-founder of the International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, Nagler led this organization between 1982 and 1992, in Vienna.

From 1992 to 2004, he founded and led the Swedish Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, renamed Civil Rights Defenders.

Nagler is a member of International Board of Austrian Service Abroad, of Media Development Loan Found, and an honorary chairman of the Council for Civil Rights Defenders. On 18 October 2011, he received the Austrian Cross of Honor for Science and Art from the Republic of Austria.

References

Books Llc (2019), Austrian Activists, BooksLlc, United States.

Source: Pescanik

Popović was born on 24 February 1937 in Belgrade. He was a Yugoslavian lawyer and political activist.

In 1961, he graduated in law from the Faculty of Law at the University of Belgrade, representing writers, artists and politicians who criticized the government of the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. In 1990, alarmed by what he considered to be the extreme nationalism of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, as well as the popular support he enjoyed, Popović created Vreme, a weekly magazine that has become one of the most prominent independent publications, featuring political themes and social, speeches by several Serbian and Croat intellectuals. In the same year, Popović led the Independent Commission to Investigate the Exodus of Serbs from Kosovo.

Between 1993 and 1994, he was a member of the Advisory Board of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in New York. He had contact with various human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and the United Nations Human Rights Committee. In 2001 joining the Serbian group on the Helsinki Human Rights Committee led by Sonja Biserko. Popović was part of several petitions, among which he encouraged the abolition of verbal crime, the end of the death penalty, and the adoption of amnesty law and the creation of a multiparty system. He died on 29 October 2013.

References

Dragović-Soso (2002) Jasna Saviours of the Nation: Serbia’s Intellectual Opposition and the Revival of Nationalism. London: C. Hurst.

“Srdja Popovic (1937–2013)“. Peščanik. 29 October 2013.

Source: The Boston Globe, 2015

Gleb Pavlovich Yakunin was born in Moscow on 4 March 1936, he was a Russian priest and dissident who fought for the principle of freedom of conscience in the Soviet Union. Gleb Yakunin studied biology at the Irkutsk Agricultural Institute, graduating from the Moscow Theological Seminary of the Russian Orthodox Church in 1959. In August 1962, he was ordained a priest and appointed a member of the parish church in the city of Dmitrov. Yakunin argued that the Church should be independent of the control of the Soviet state and was therefore banned and removed from its functions in May 1966. In 1976, he created the Christian Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Believers in the USSR, publishing hundreds of articles on the suppression of religious freedom in the Soviet Union. As a result, in August 1980, Yakunin was arrested and convicted of anti-Soviet ideals, being held in the KGB prison in Lefortovo until 1985, and then in a forced labor camp known as “Perm 37”. In March 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev granted him an amnesty and he could return to Moscow. In 1990, Yakunin was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation and served as vice president of the Parliamentary Committee for Freedom of Conscience. He coauthored the “freedom of all denominations” law that was used to open churches and monasteries across the country. He created the Committee for the Defense of Freedom of Conscience in 1995. He died at the age of 78 on 25 December 2014.

References

Rusak Vladimir, Gleb Yakunin, Sergei Pushkarev (1989), Christianity and Government in Russia and the Soviet Union: Reflections on the Millennium, Westview Press

Source: Arno Mikkor, 2017

Antoni Macierewicz was born on 3 August 1948 is a Polish politician and former Minister of National Defense. Macierewicz was one of the founders in 1976 of the Committee for the Defense of Workers, a leading anti-communist opposition organization that was a precursor to Solidarity. During the 1980s, he was director of the Solidarity Social Research Center and was one of the union’s main advisers. A former political prisoner, he escaped from prison and remained hidden until 1984, publishing clandestine publications. He held the position of Minister for Internal Administration from 1991 to 1992, and the Head of the Military Counterintelligence Service from 2006 to 2007. He was a Member of the European Parliament from 23 April 2003 to 19 July 2004 and was appointed Minister of National Defense from 2015 to 2018. He is currently in his sixth term in the Polish Parliament, where he represents the Piotrków Trybunalski district.

References

Bernhard, Michael H. (1993), The Origins of Democratization in Poland: Workers, Intellectuals, and Oppositional Politics, 1976-1980, New York, Columbia University Press.

Michael Szporer; Mark Kramer (2012), Solidarity: The Great Workers Strike of 1980, Lanham, Lexington Books.

Source: Saša Uhlová, 2015

Petr Uhl was born on 8 October 1941 in Prague and graduated in mechanical engineering at the Czech Technical University. He was one of the founders of Charter 77 and one of the founders of the Committee for the Defense of Unjustly Prosecuted. Consequently, he was fired in 1977 and sentenced to five years in prison in 1979. After the Velvet Revolution, he worked at the Coordination Center of the Civic Forum, and after the June 1990 elections, he held the place of the Chamber of the Peoples of the Federal Assembly. After the disintegration of the Civic Forum in 1991, he joined the parliamentary club of the Civic Movement, remaining in the Federal Assembly until the 1992 elections. From 1990 to 2000, he was an expert at the Geneva Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at the United Nations Commission, from February 1990 to September 1992, he served as Director-General of ČTK / ČSTK. He worked until 1996 as editor of the bimonthly Listy Jiří Pelikán and, later, from 1996 to 1998, he was editor of the daily Právo. Between 1998-2001, he has President of the Council for Nationalities and the Human Rights Council He has been a member of the Green Party since 2002.

References

“Memory of Nations: Ing. Petr Uhl” in https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/uhl-petr-1941

Source: Encyklopedie Prahy, 1999

Václav Benda, a Catholic activist and intellectual and mathematician, was born on 8 August 1946, in Prague. PhD in Philosophy at Charles University in Prague, he saw his academic career end when he refused to join the Communist Party in the early 1970s. Benda was an advocate of the movement against the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic and, in 1977, became a signatory to Charter 77, which led to his imprisonment in May 1979 until 1983. After his release, he resumed his role as spokesman for the group of Charter 77 and is also a founding member of the Commission for the Defense of Unjustly Judged (VONS). From 25 June to 31 December 1992, Benda was President of the Chamber of Nations and from 1991 to 1998, he was head of the Department of Investigation of the Crimes of Officials of the Communist Party. In 1996, he was elected to the Czech Senate, a position he held until his death in 1999.

References

Benda, Vaclav (2018), The Long Night of the Watchman: Essays by Vaclav Benda, 1977-1989, United States, St. Augustines Press

Danuška Němcová, was born on 14 January 1934. Czech psychologist, dissident from the communist regime and one of the first signatories of Charter 77. In the 1950s, she studied psychology at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University. In 1978, together with the other signatories of Charter 77, she created the Committee for the Defense of the Unjustly Persecuted (VONS). In 1979, she was arrested and spent half a year in custody. In January 1989, at the beginning of “Palach Week”, Dana Němcová was arrested on her way to the Holy Monument to Wenceslas to place flowers as a speaker for Letter 77. In November 1989, she became a co-founder of the Civic Forum and in 30 January 1990, she held the position of deputy in the House of Commons, moving to the Civic Movement in 1991, after the extinction of the Civic Forum. She headed Havel’s Goodwill Committee and worked for the Refugee Counseling Center. In 1990 she received the prize from the international Catholic peace movement Pax Christi and, in 1998, she received the Presidential Medal of Merit. An advocate for psychological and legal assistance to refugees, in 2000 she received the Middle Europe award and worked at the Refugee Counseling Center and Center for Migration Issues. In 2016, he received the Arnošt Lustig award.

References

“Memory of Nations: Dana Němcová” in https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/nemcova-dana-1934

Source: Courage – Connecting Collections

Bärbel Bohley, German artist and political activist, known as the “Mother of the Revolution”, was born in Berlin on 24 May 1945 in the German Democratic Republic. In 1982, together with some 150 women, fought against the 1982 recruitment law, which included a provision that made women responsible for military service. Titled “Women for Peace”, Bohley and the group were determined to launch a strong protest the militarization of GDR society. Bohley was arrested and served two months. She continued to work with activists from the political left being considered by Stasi agents as a threat to the SED dictatorship. On 11 September, Bohley and Ulrike Poppe founded the New Forum which aimed to reinforce the need for immediate reforms through dialogue with all dissidents. More than 200,000 people signed the New Forum manifesto calling for dialogue and change. A month later, Honecker was removed from office. In the first democratic elections held in the GDR in March 1990, the New Forum participated as a movement, and not as a conventional political party, allied with “Democracy Now” and the “Peace and Human Rights Initiative”; the three campaigned as “Alliance 90”. Despite the combined effort, they won only 2.9% of the vote. Bärbel Bohley decided not to participate in the political life anymore, dedicating herself to her activity as an artist. She died in September 2010.

References

Philipsen, Dirk (1993), We Were the People: Voices From East Germany’s Revolutionary Autumn of 1989, Durham, Duke University Press.

“Bärbel Bohley” in https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/bohley-barbel-1945

Source: Peace Post

Peter Benenson was born in London in 1921. He studied law at Oxford and later joined the British Labor Party. On 28 May 1961, in The Observer newspaper, published a long article entitled, “The Forgotten Prisoners”, which suggested an appeal for the 1961 amnesty, in which he asked governments to release their political prisoners or to hold fair trials. Amnesty’s first campaign in 1961 highlighted the fate of six prisoners of conscience: the leader of the angolan anti-colonialist resistance Agostinho Neto; the greek communist Toni Ambatielos; archbishop Josef Beran of Prague and cardinal Jozsef Mindszenty of Budapest, arrested by communist dictatorships; an advocate for black rights in the United States, Ashton Jones, and the Romanian philosopher, Constantin Noica. The article reached a worldwide reach, giving rise to the creation of Amnesty International, an organization that defends human rights and that still exists today. Benenson died on 25 February 2005, in Oxford, aged 83.

References

Benenson Society official site https://www.benensonsociety.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3&Itemid=4

Winner, David (1992), Peter Benenson: Taking a Stand Against Injustice Amnesty International, New York, Gareth Stevens Pub.

Winner, David (1991), Peter Benenson: The Lawyer Who Campaigned for Prisoners of Conscience and Created Amnesty International, London, Exley.

Source: E-International Relations, 2017

Mary Kaldor is an English scholar, born on March 16, 1946. Mary Kaldor was one of the main member founders of European Nuclear Disarmament (END) and Helsinki Citizen’s Assembly, a non-governmental citizen organization dedicated to peace, democracy and human rights in Europe.

At this moment, she is already withdrawn from Education, but she was a professor of Global Governance and director of the research group in “Civil Society and Human Security” at the London School of Economics. Professor Kaldor was a pioneer in the concept of new wars and global civil society, and her work in the practical implementation of human security directly influenced European and national politics.

Kaldor is the author of many books, including “The Ultimate Weapon is No Weapon: Human Security and the Changing Rules of War and Peace”, “New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era” and “Global Civil Society: An Answer to War”. Her most recent book, with co-authorship of Professor Christine Chinkin, was published in May 2017 and it is entitled “International Law and New Wars”.

At the request of Javier Solana, EU High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy, Mary Kaldor organized a study group on European security. From this group came the well-known Barcelona report, “A Human Security Doctrine for Europe”, of September 2005, and also a subsequent report “The European Way of Security”.

Professor Kaldor received several honorary professor titles and an award in 2015 for academic achievements in the field of peace. His work was recognized, in 2003, with the prize of the Order of the British Empire, “for services to democracy and global governance”.

References:

Entrevista ao jornal “The Gaurdian” de Mary Kaldor. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/apr/01/mary.kaldor.interview

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/international-law-and-new-wars/24BDAF25289439847296D00B0DA4B3A4